This week, I’m thinking out loud about the right to ignorance, and if there is such a thing. I don’t think it goes that well, but read on anyhow.

***

I was listening to Science Friday’s interview of Deborah Zoe Laufer last week, about her play “Informed Consent.” In part it tells the story of the Havasupai tribe of Native Americans, who (as I understand it anyway), because of their dwindling numbers and relatively high diabetes rate, agreed to have their genome mapped to see if they could find out why and if there was anything that could be done to help. What additionally took place was that the scientists involved also found data that suggested the Havasupai people originated in Asia, some untold thousands of years ago. And as she explained it, finding this out really upset them.

Because in their mythology, they were made in the Grand Canyon.

In the interview Laufer says “what was most devastating to them was having their story taken away from them… their creation story.”

And it made me stop and think: is that even possible, to take away a people’s mythology? And if it is, do people have a right to ignorance?

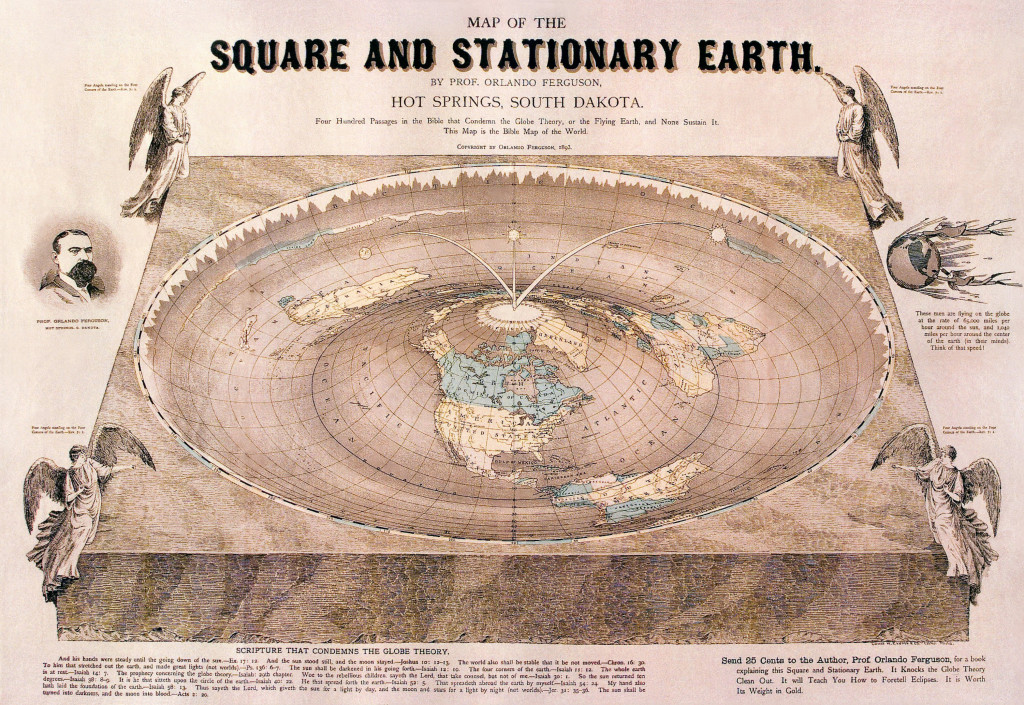

Because the story isn’t true. They were, I can pretty much assure you (barring these guys being right), not “made” — in the Grand Canyon or elsewhere. Like every other human alive on this planet today, they were born, the descendants of earlier hominids, still earlier mammals, and well before even that, from once-celled organisms in the primordial goo.

Now, the use of their genetic data without their informed consent isn’t what I’m talking about here, because I think that no, you shouldn’t be allowed to do research not specifically asked for using someone’s DNA. But it didn’t take their DNA to disabuse them of their creation myth — basic science had, at least in theory, done that long ago.

So: does a group, of any kind, have a right not to be told true things?

I have always thought that beliefs do not deserve to be coddled and cooed over like babies. Beliefs do not deserve protection in the courts. Beliefs must be allowed to stand on their own in the vast world of ideas and be held or not for whatever reasons the people holding them choose.

Does any human being have the right to believe things as they see fit? Yes. If you want to believe that the moon is made of cheese, I can think you’re wrong (I can think a lot of potentially unflattering things about you besides), I can tell you you’re wrong, but I can’t stop you from choosing to ignore me. But by the same token, you cannot tell me I’m not allowed to tell you that the moon is actually a small planetoid made of, well, rock and dust and, well, things the moon is actually made of. We can have an argument about it. We can agree to disagree. We can bang our heads against proverbial walls lamenting that the other won’t listen. But do either of us have a right not to be told what the other views as truth? Not a right to prefer not to be told. Not a right to refuse to believe what you’re told. But a right not to be told at all? I really can’t see the answer being yes.

And then there’s the other part I can’t wrap my head around: how do you “take away” someone’s story?

The Answers in Genesis folks have been told their creation myth is patently wrong over and over and over, but they’re still holding on to it. But, maybe not everyone’s beliefs are so stalwart?

It is possible you could value truth, respect the scientific method on which that truth is based, and then be upset by what you find? I suppose the answer must be yes; there must have been scientists in the past upset by a discovery because it challenged their worldview. Could you be afraid of learning the truth because you might not like it? Again, I suppose the answer to that must be yes. Could you thus choose to never learn anything new in case it changes the way you see the world? Well, you could certainly try.

But should your choice to be ignorant of the facts be protected?

I’m baffled. As a skeptic, I value the truth above all else. Pleasant or unpleasant, if you ask me if I want to know the truth of a thing — do I have cancer? How long will I live? Is Pluto really not a planet? — the answer will always be “yes, and show me how you know.” We can disagree on the truth, of course, but I will always seek it out. And so trying to imagine a worldview in which someone could honestly say “I prefer my comforting ignorance” is borderline impossible for me. Especially because in my experience, the people who prefer their ignorance tend to display a remarkable inoculation against the truth, regardless.

I find myself limited to my own particular understanding of the world. I try to imagine a scenario like the one above: say aliens arrive on Earth, and tell us that our science misunderstands something fundamental, that disabuses us of a notion very important to us. I can’t imagine what that might be, because it’s hard to know where one’s fundamental ignorance lies, but again, my worldview prevents me from being interested in preserving beliefs that are wrong. So: I would want to know, regardless of what it is.

For me, ignorance is never bliss, it’s just the absence of useful information on which I could base my actions.

Do you have a right to believe what you like? I suppose. But do you have a real, genuine right to not be told the truth?

Maybe it’s a personal failing, but I can’t imagine why you would.

***

Richard Ford Burley is a writer, library worker, and doctoral candidate in English at Boston College, where he’s studying remix culture and the processes that generate texts. In his spare time he writes about science, skepticism, and feminism (and the preservation of ignorance) here at This Week In Tomorrow.