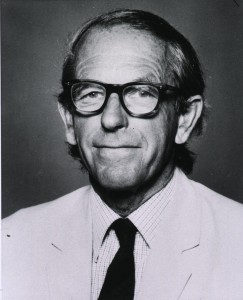

Dr. Frederick Sanger died this week at age 95. One of only four people to have ever won two Nobel prizes — and the only person ever to have won two for chemistry — Dr. Sanger’s work is responsible for our current understanding of the human genome. First working on the structure on insulin, and then moving on to that of DNA, he opened up new horizons in biology and medicine. It would be little exaggeration to call him the father of modern genetics.

Frederick Sanger was born on August 13, 1918, in Rendcomb, a village in the Cotswolds, in Gloucestershire. He was the second of three children — he had an older brother Theodore, and a younger sister Mary — and his Father (also Frederick), was a small-town physician and a Quaker.

Despite the current climate in scientific-religious relations, Sanger’s Quaker upbringing seems to have had a profound effect on his life. In a 2001 interview, Dr. Sanger explained that he had taken two things from his father’s religion, things he carried with him all his life, although he himself was never a member of the Society of Friends.

The first of these was his pacifism. In 1940, Sanger was exempted from military service as a conscientious objector, and indeed, it was through his commitment to pacifism that he met Joan Howe, the woman who would later be his wife. Both were members of the Cambridge scientists’ anti-war group.

The second was an almost pathological devotion to the truth, which he saw as both the driving force behind his science, and as a way of relating to the world. He said that commitment to the truth “was very important for a scientist, because a scientist is really studying truth.” He also admitted to having “a sort of fixation about it,” saying that when asked even a casual “how are you?” he found it “a little difficult” just to say the expected “fine, thanks,” if it weren’t the case.

In 1958, Dr. Sanger won his first Nobel Prize, “for his work on the structure of proteins, especially that of insulin.” By using a dyeing reagent, dinitrofluorbenzene (now known as Sanger’s Reagent) he was able to determine the exact sequence of the 51 amino acids that made up the insulin molecule. Not only was this useful knowledge in and of itself, but his methodology was a new process: “sequencing proteins” was now something that could be done.

The Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1980 was for a wave of new work on DNA, and it was divided three ways. One half went to Professor Paul Berg, of Stanford University, “for his fundamental studies of the biochemistry of nucleic acids, with particular regard to recombinant-DNA.” The other half Dr. Sanger shared with Professor Walter Gilbert, of Harvard University, “for their contributions concerning the determination of base sequences in nucleic acids.” For his part, Sanger sequenced the 5735 nucleotides of the DNA of a bacteriophage (phi-X174 — the same one Craig Venter’s team created from scratch in 2003). And again, the process was the key point — Sanger’s work on sequencing DNA later led to the successes of the Human Genome Project, and well as to the routine screenings that allow us to do everything from fight cancer to explain our preferences regarding cilantro today.

By winning a second Nobel Prize, Sanger joined an elite club. The other three names you’ll also recognize: Marie Curie (radioactivity; radium and polonium); Linus Pauling (chemical bonds; anti-nuclear peace activism); and John Bardeen (invented the transistor and BCS theory).

Yet Dr. Sanger’s successes never overcame his humility. In 1981 Sanger turned down a knighthood, by some reports because he didn’t like the idea of being called “sir.” On the evening of his first Nobel banquet, Dr. Sanger addressed a crowd of university students as “fellow students,” hoping that they would allow him that address because, in his words, “I still consider myself a student, and this I regard as a great privilege.” When he won his second Nobel Prize in 1980, he still felt the same.

“When I was here 22 years ago I addressed the students of 1958 as “fellow students” because although I was 40 years old I still felt that I was one of them, and I still feel the same today. I and my colleagues here have been engaged in the pursuit of knowledge. We have been learning, are still learning and I hope will continue to learn.”

To say we could all stand to learn from his example would be an understatement.

Dr. Sanger is survived by his three children, Robin, Peter, and Sally, and by a new world of possibility thanks to his diligent and brilliant work.