There’s been so much Rosetta news this week that I’ve decided it deserves its own post (otherwise there won’t be any room for all the other news tomorrow). Here’s the rundown on the little spacecraft that made all the news this week.

***

In 2004, ESA launched the Rosetta mission with the deceptively simple task of catching a comet and learning all we could about it. That mission is still ongoing, but this week a lot happened, including what was arguably the most challenging part of the mission, setting down the lander, named Philae, on the surface of the comet, and doing a lot of scientific work that could only be done in direct contact with a comet. Everything didn’t go exactly as planned, but even so the mission has been so full of successes, surprises, and firsts that it’s really worth going over.

Rosetta was supposed to launch in 2003, to chase an entirely different comet known as 46P/Wirtanen, but with the worries and delays following a communications error in another rocket in 2002, that plan was abandoned in favour of another: another launch date, and another comet.

That new comet was this one: 67P / Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Discovered in 1969 by Soviet astronomers Klim Ivanovych Churyumov and Svetlana Ivanovna Gerasimenko, at its fastest it flies at around 135,000 kilometres per hour (that’s 84,000 miles per hour if that’s what you’re into), and makes its way around the sun about once every six and a half years.

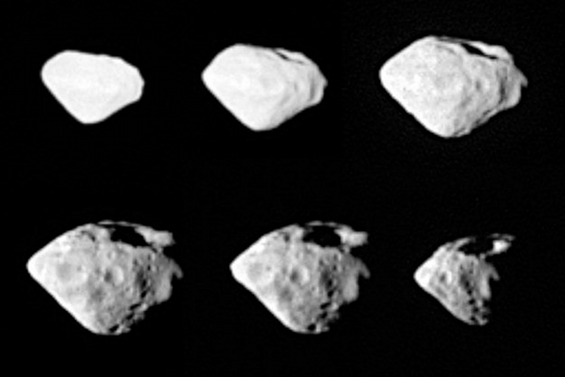

In 2008, on its long journey through space (that involved a number of passes by planets to harvest their gravity for its speed boosts), it snapped shots of an asteroid called 2867 Steins, an irregular belt asteroid that’s about 6.7 kilometres wide at its widest point. You can read more about that here.

When it finally caught up to 67P this August, they discovered that it’s a rather odd duck of a comet. It’s got two distinct “lobes” joined by a “neck,” which has led commentators to say it looks like a rubber duck. That was a surprise, and one that would make for a lot of new calculations. Imagine how hard it is to get into orbit of something with almost no gravity, then imagine the object is so irregular that it’s gravity has peaks and wells. Nevertheless, they managed it, and by early August it was the first time we’d ever entered into orbit around a comet.

Scientific measurements started to pour in from Rosetta’s sensors. Among other things, they found out that 67P stinks. Literally. The comet gives off far more ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, formaldehyde, and methanol than expected at this point in its journey around the sun. On top of that, the comet was singing to us. Rosetta’s magnetometers picked up oscillations in the comet’s magnetic field and we’re still not 100% sure what’s causing them. But you can listen to them here.

As Rosetta got closer and closer, the images poured in, and the team turned to picking a landing site for the little lander Philae. By early November that task was accomplished, and on November 12, this Wednesday, they sent down Philae.

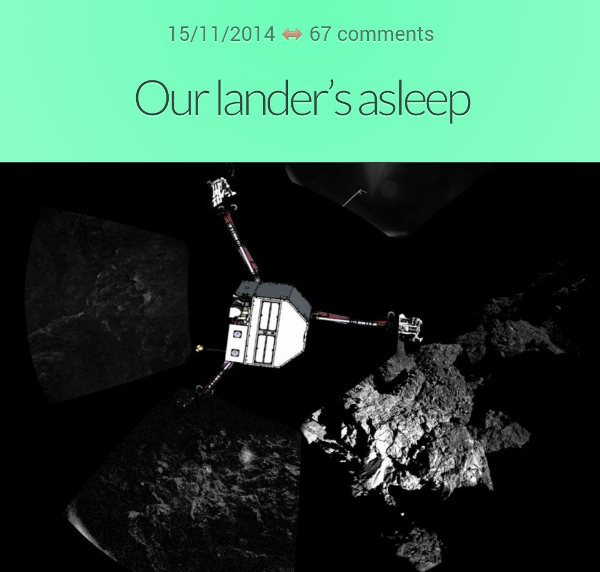

At first it seemed that everything was great: Philae reported back that it had landed and was doing okay. Randall Munroe (of xkcd fame) even did a series of images to follow the lander’s progress (turned into a gif here). But all was not well. The harpoons it was trying to use to affix itself to the surface of the comet hadn’t fired, and as a result it had bounced — a long way. When gravity is that low, a bounce can take you over a kilometre. Philae eventually did land again, but not as planned: by the edge of a crater, the little lander wasn’t enough in the sun to power itself. Instead of 6-7 hours of sunlight, it was only getting 1.5 a day. The batteries were running dry.

They had maybe 60 hours of battery power to work with, so they got to work. Without the harpoons fixing it to the surface, there was still a chance that using the drill or the hammers might shift the lander into a better position, but sadly it was not to be. A lot of good data were collected, and we’re still sorting it out (and will be for some time), but as of this morning, the little lander that could has gone to sleep.

But all hope isn’t lost: just before it shut down, the ESA team were able to rotate and lift the panels such that maybe — just maybe — in the coming days, weeks, or months, Philae may get enough juice to wake up again and do a little more science for us folks back here on Earth. In the meantime, Rosetta’s still orbiting 67P, and will follow it as it approaches the sun and begins to stream off its contents into space.

For now, we’ll wait and watch, and see what other sights await us on this fascinating mission.

See you all tomorrow for the weekly roundup.

One thought on “Rosetta Special Issue | Vol. 2 / No. 2.2”

Comments are closed.